A vivid description of a German wedding in Chanhassen

Here’s a little bit of the fatherland, not more than 20 miles from the Court House tower, where German is the language spoken and where the customs of the people suggest the Schwarzwald. Why go abroad when you may visit Chanhassen instead and perhaps be one of a Merry Wedding Party?

As you approach Chanhassen from any direction, whether eastward from Excelsior, northward from Shakopee, westward from Eden Prairie or, if you know the secret woodland trail, southward from hidden paths along Christmas and Long Lakes, you are impressed by the dominant steeple of St. Hubert’s church.

St. Hubert is the patron of the chase, and on the central altar of the little church is his image with its arm resting on the neck of a fawn. When the parish was established a good many years ago St. Hubert seemed the most appropriate saint to become the protector of this little church in the woods.

Chanhassen is a German settlement, and German is almost the only language heard among the villagers and the farmer folk from the surrounding country who drive in for mass on a Sunday morning and linger for a bit of neighborly gossip before hitching their sturdy teams to wagons, buggies and carryalls and driving home again.

You cannot even walk through Chanhassen without catching a suggestion of its Bavarian atmosphere. It is, unfortunately, rather too closely connected with American civilization by the main line of the Milwaukee Road, but the tracks run through a sort of shallow gully and when no trains disturb the quietude the pedestrian, and even the motorist, may imagine himself in some friendly settlement in the Schwarzwald or the foothills of the Alps; though for mountains he would have to substitute the distant blue ridge which marks the valley of the Minnesota River six or seven miles to the southward.

Once in a while Chanhassen has a wedding. Then, if you happen to be passing through the town, or, better still, if you enjoy the rare privilege of being an invited guest, you need no imagination to put yourself across the Atlantic into some secluded community far from the strides of commercial progress and those modern advances which, as they grind along, level all the dear and quaint distinctions that separate country from country and province from province.

The ceremonies of marriage and burial are still the most important individual events in this changing world; and the rituals that mark their occurrence are, consequently, the last to give way to changes that threaten to make human life one colorless monotony of system and efficiency.

Being in Chanhassen on this perfect July day recalls very vividly a wedding which I attended here a few years ago in early summer. Having just had dinner with the fair heroine of that event, and held her baby on my knee while she washed the dishes, I may, perhaps be excused for a few reminiscences of that May day when a friend and I, after walking five miles through the dewy woods vocal with the mating songs of birds, put on our collars and neckties in the village tap room and went to the wedding.

The two streets of the town were already filled with teams that had brought guests from many miles around, though it was not yet 9 o’clock. Down every approaching road clouds of sunlit dust indicated the coming of more friends. The home of the bride’s parents stood well back from the road in a shadowed, uncut lawn, whereon men, women, and children in their unaccustomed best stood in festive talk and laughter, greeting one another and bantering the tall young bridegroom who looked highly uncomfortable in a black coat with a huge bunch of flowers tied to a lapel with a pendant white ribbon.

The chatter and the friendly chaffing, all in German (including the laughter), the old land maenner and hausfrauen, who had broken the wilderness, the younger men and women who had left plough and churn to come to the wedding feast and the boys and girls who would be next to take up the beautiful heritage of normal daily labor, the flooding sunshine, the sweet May wind and the chiming church bells all blended dreamily into the remembered strains of Goldmark’s “Rustic Wedding” music.

But now the imagined music changes to the melody of Grieg’s “Bridal Procession,” for the wedding party is coming from the house. Silence falls on the guests in the yard and they form into two lines from the porch to the gate. Down the lane thus formed come two children in white with great bouquets.

Following them are the bride’s maids in muslin and ribbons, carrying flowers also, not only in their hands but in their eyes and cheeks. Behind them walk the awkward groomsmen, to whom no one pays any attention because now can be seen the bride herself on her father’s black-sleeved arm.

She is beautiful as all brides are, with the right light in her eyes, and the right happiness in her smile, the right spring in her step and the right calmness on the fair brow from which hangs the long veil, caught with orange blossoms on the temples and floating in the perfumed wind.

Her mother leans on the arm of her new son, and the little procession crosses the yard and turns down the street toward the church, where the bells are ringing clearly, almost drowning the songs of orioles and robins who seem to have gathered in unusual numbers to make music on this happy morning.

All the guests follow and fill the little church during the long and solemn Roman ceremony, when the procession forms again, this time with the bride on her husband’s arm. All return to the house and the yard, for the house will not hold them all, and the festivities begin.

For days and days the women of the family, even unto the fourth and fifth cousins, have been baking, boiling, stewing and mixing rich German viands for the wedding feast. The bride’s mother, protesting in vain, is put out of her own kitchen, over which she has presided for 40 years, and is given a seat of honor on the porch where she is instructed to stay and keep her black silk dress clean. She doesn’t enjoy it at all, and casts uneasy glances toward the closet where her big apron hangs and toward the kitchen where her neighbors and friends have taken impertinent charge.

The wedding breakfast begins at 10:30 and continues, in relays, until 2 in the afternoon, during which time more than 300 people are bountifully fed in a dining room that, at a pinch, will seat 25 at one time. Memory struggles in vain to remember the names of half the wonderful dishes served at that so-called breakfast! Even a German dictionary wouldn’t include them all.

Outdoors in the yard a platform has been built by the bride’s father 40 feet square (the platform, not the bride’s father, though the dimensions are ample), and over it a canvas roof to protect dancers from the sun and possible rain. The band from Shakopee is coming at 4 o’clock to play for dancing, but bless you, eager young hearts and feet cannot wait until that time; so a local genius who plays the accordion is impressed into service and the dancing begins before noon. There are polkas, waltzes, quadrilles and old German contra-dances; the floor is crowded to good natured suffocation and the dancing once started, continues without intermission until 5 o’clock the next morning, the Shakopee band and the accordion virtuoso spelling each other through the long, yappy, rhythmic hours.

Just beyond the dancing platform is a spotless new house, the bride’s wedding gift from her father.

A wagon shed adjoining the big red barn ha been converted into an open bar and here all day and all night, four husky volunteers open fresh kegs of foaming, amber beer serving it to all comers and sending great, dripping trays around among the guests in the house, on the porch where the old men are playing sixty-six and pinochle, in the yard and in the dancing pavilion.

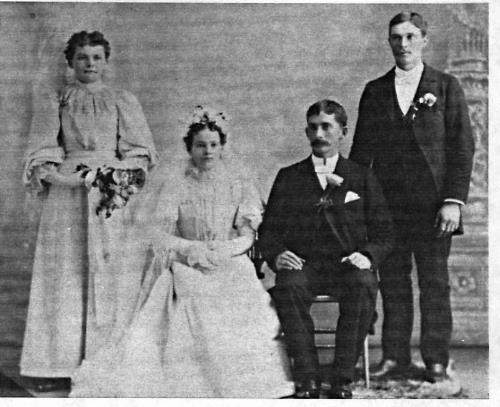

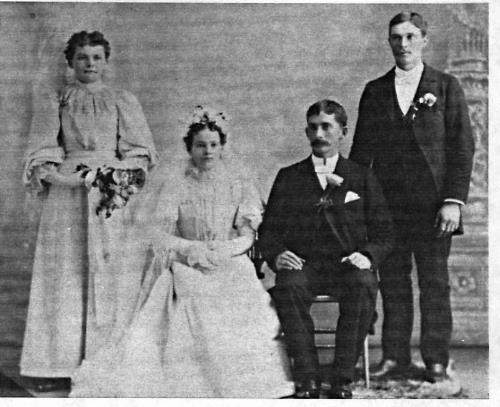

For a short time in the afternoon the bridal party disappears and drives over to Shakopee for the important duty of having the wedding photographs taken; the groom sitting, and the bride standing wither hand on his shoulder.But they soon return to join the fun and country swains fight for the honor of leading the laughing bride through the mazes of a dance.

This is a Chanhassen wedding, taking place in Minnesota not 20 miles from the City Hall tower in Minneapolis; and as I sit here three years later with the bride’s bouncing baby on my knee, I think of the people who complain because they are too poor to take a trip to Germany and wonder why they don’t enrich themselves by adopting the slogan: “See Chanhassen first.”

Compiled by Mark W. Olson

Writer: Caryl B. Storrs

Year: 1916

What: A vivid description of a German wedding in Chanhassen.

Published: Originally published in the Minneapolis Tribune, then reprinted in the book “Visitin’ ‘round inMinnesota.” The book includes short stories on several towns throughout the state. Storrs gives this description: “The inconsequent sketches included in this book represent a portion of a most interesting summer spent in rambling over this wonderful State of Minnesota.” A portion of this story was reprinted in “Chanhassen: A Centennial History.”

Photo: Chanhassen Historical Society Archives: Lambert and Anna (Driessen) Weller's wedding - 1897